Some moments cling to the bones, refusing to fade no matter how many years or lifetimes pass. They do not dissolve with reason or prayer; they simply haunt, like a question that can’t be answered. For Rowan Hart, that moment arrived on the coldest morning of his life — the morning he watched the flames rise around the woman he loved, and saw something move that should not have moved.

Before the fire, before the silence, before the unthinkable, there had been love. Real love — the kind that made ordinary mornings shimmer. Rowan, a soft-spoken architect from an old New England family, had met Nyla Carter in the least romantic place possible: the hospital where his father was dying. Nyla had been the attending nurse, calm and capable, her kindness worn not like a badge but like skin — natural, effortless, unshowy.

The first time Rowan saw her, she was adjusting an IV drip with gentle precision, humming under her breath, completely unaware that someone had fallen in love with her in that exact moment. After his father’s passing, Rowan kept finding excuses to visit the ward again, first to sign documents, then to deliver flowers to “the staff.” It took Nyla weeks to realize the flowers were always for her.

They were married a year later, in a small garden behind the house she grew up in. The ceremony was simple, radiant, and utterly unapproved of by his family. His mother, Beatrice Hart, had refused to attend. “She doesn’t belong in this family,” she had said, her voice soft but edged like glass.

“And neither will that child.” Those words, spoken before Nyla was even pregnant, left a chill that lingered. Rowan tried to shield his wife from the disdain, but Beatrice’s influence was like ivy — slow, creeping,

impossible to fully uproot. She would visit their home unannounced, her expensive perfume arriving before her, bringing with it an atmosphere that seemed to drain warmth from the walls. Nyla, ever gracious, would smile and offer tea. Beatrice would drink it, glance around the modest house with cold amusement, and say things that seemed kind until you looked closer. “You’ve made it… cozy here,” she once murmured. “A pity the Hart family name won’t fit as neatly.”

When Nyla became pregnant, Rowan thought perhaps his mother’s heart might soften. Instead, her visits became more frequent, her comments sharper, her smiles more surgical. She brought gifts — tiny cashmere blankets, a silver spoon engraved with the Hart family crest — and under the veneer of generosity lay venom.

“I only want what’s best for my grandchild,” she said one afternoon, her voice honey-smooth. Nyla had nodded, exhausted and polite, but Rowan saw how she avoided his gaze afterward, as if afraid to voice what she was truly feeling. The tension had become an unspoken third presence in their home, invisible but heavy.

Then came the morning that changed everything.

Beatrice arrived unannounced again, dressed in black as if attending a funeral rather than a visit. In her hand, she carried a small porcelain cup covered with a lace napkin. “It’s an old family recipe,” she said cheerfully. “For the baby. My mother swore by it.” Nyla hesitated, but Beatrice’s expression left no room for refusal. So she drank.

Less than an hour later, she collapsed in the kitchen.

Rowan heard the crash from upstairs — a sound that tore through the quiet like thunder. He found her crumpled on the floor, the cup shattered beside her, her skin pale as marble. Her lips moved, trying to form his name, but no sound came. The ambulance was a blur, the hospital an echo. Doctors swarmed, machines screamed, and somewhere in the chaos, Rowan lost his grasp on time. When it was finally over, when a doctor with weary eyes stepped into the waiting room and said the words no one should ever have to hear, something inside him fractured. Both Nyla and the baby were gone.

For two days, he moved like a ghost — eating nothing, sleeping not at all, drifting through rooms still scented faintly of lavender and tea. When the hospital called about funeral arrangements, Rowan could barely speak. “She wanted to be buried,” he managed to whisper. “She was afraid of fire.” But Beatrice, efficient as always, stepped forward with the kind of calm that made the hair on the back of his neck rise. “Cremation is tradition in our family,” she said gently. “It’s purifying. Let her rest with dignity.” Rowan wanted to protest, but he couldn’t find the strength. He signed the papers she handed him, and just like that, Nyla’s final wish was erased.

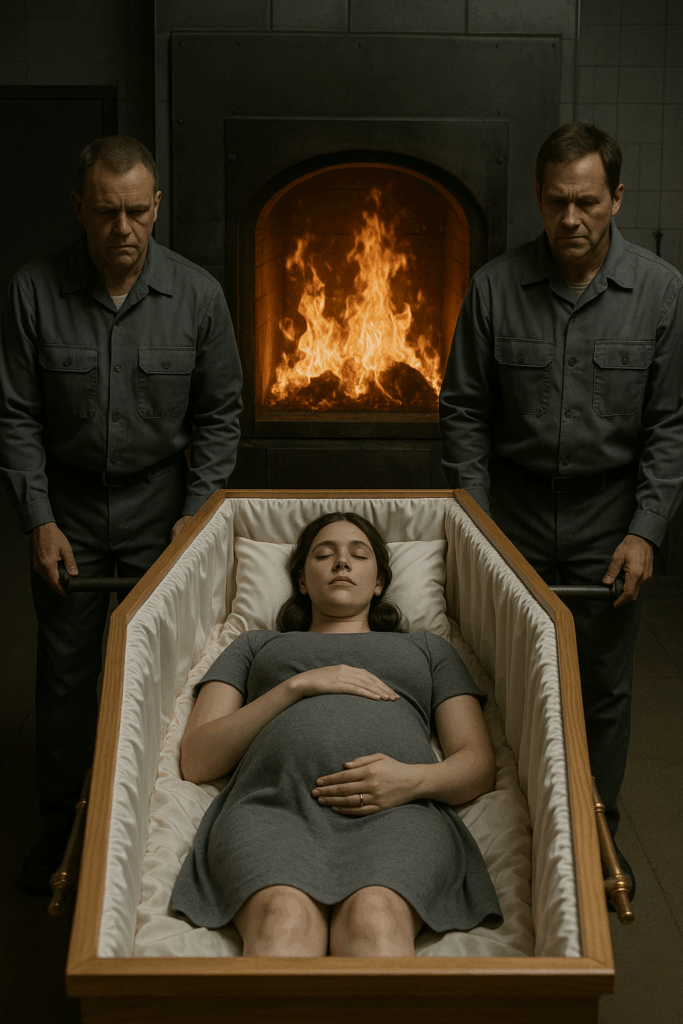

The cremation took place the next morning. The sky hung low and gray over the old stone crematorium at the edge of town. The smell of rain was in the air, though no rain fell. Rowan stood before the stretcher, staring at the woman who had once filled every corner of his world with light. Nyla’s face looked peaceful, her hair brushed neatly, her lips tinted faintly pink — as if she were only sleeping. Her hands rested over her slightly rounded belly, and for a terrible, fleeting second, Rowan almost convinced himself that she might stir, open her eyes, and ask what was happening.

Beatrice stood behind him, hands clasped, a faint smile on her face that never reached her eyes. “Say your goodbyes,” she whispered. “It’s time.”

The priest began to speak, his words hollow in the cavernous space. Rowan’s heart pounded in his ears. He wanted to reach out, to touch her one last time, to promise her that he would love their child even if he had to do it alone. But as he leaned closer, something stopped him. A faint ripple — a movement so small it could have been imagined — fluttered beneath the silk shroud covering Nyla’s belly.

He froze. His breath hitched. Had he really seen it? The priest’s voice droned on, and the furnace began to hum. Then it happened again. A slow, unmistakable shift — as though something inside had pressed outward.

Rowan stumbled back. “Wait!” he shouted. “Stop! She moved!” His voice cracked with raw panic. “Her stomach—she’s alive!” The priest looked startled, the attendants confused. Beatrice’s expression, however, didn’t change. She stepped forward quickly, her hand gripping his arm with surprising strength. “It’s just gas,” she said sharply. “Muscle reflex. It happens after death.” Her tone was controlled, almost rehearsed. “She’s gone, Rowan. Let her go.”

“But—” He struggled against her grip, desperate. “Please, just check! I saw it—”

Beatrice leaned in close, her perfume thick and cloying. “You killed her,” she whispered. “Don’t make this uglier than it already is.”

Something in her voice broke him. The attendants hesitated, uncertain, but Beatrice gave a single, commanding nod. The furnace doors closed.

The sound of the flames filled the silence.

That night, Rowan couldn’t sleep. Every time he closed his eyes, he saw the movement again, the faint curve of fabric shifting over still flesh. He tried to tell himself it was impossible — that the doctor had confirmed her death, that his mother was right. But he remembered the warmth of her hand when he’d touched her that morning. Not cold. Not dead. Warm. Alive.

The next day, he called the hospital, his voice trembling. “Are you sure?” he asked the doctor. “Are you absolutely certain she was gone?” The doctor’s answer was polite, detached. “We followed all necessary procedures, Mr. Hart. There was no sign of life.” Rowan hung up before the man could finish. He sat in silence for a long time, the phone heavy in his hand, and somewhere in the back of his mind, he swore he could still hear it — the faint rhythmic pulse he’d heard through the flames. A heartbeat.

Three days later, an envelope arrived in the mail. No return address. Just his name, written in soft, looping handwriting. Inside was a single note:

“She told me she felt dizzy after drinking something her mother-in-law gave her. I didn’t think much of it then. I’m sorry.”

It was signed by Nurse Clara Hale — the nurse who had been with Nyla in her final moments. Beneath her name was a phone number.

Rowan called immediately. When she answered, her voice was trembling. “Mr. Hart? I shouldn’t be telling you this, but something wasn’t right. Her toxicology report came back yesterday. There were traces of digitalis — foxglove extract — in her system. It’s a heart stimulant in small doses, but it can stop the heart entirely if too strong. I think…” She hesitated. “I think someone poisoned her.”

Rowan’s pulse thundered in his ears. “And the baby?” he whispered.

The nurse’s voice lowered to a whisper. “Her baby still had a heartbeat for several minutes after she was declared dead. We didn’t realize until it was too late.”

That night, Rowan broke into the crematorium.

Rain lashed against the windows as he forced the lock and stepped inside. The room smelled of metal and ash. He searched the shelves until he found it — a small bronze urn with a brass plate engraved: Nyla Hart. His hands shook as he opened it. Beneath the gray ash was something small and half-burned — a locket. Inside, he found a faded photograph of the two of them on their wedding day, folded tightly around a crumpled ultrasound image dated one day before her death. Beneath the scan were four words, written in Nyla’s unmistakable handwriting:

“She’s still in there.”

He confronted Beatrice the next morning. She was in her garden, trimming white roses, her movements precise and almost serene. “Why did you do it?” he demanded. She didn’t flinch. “Because you were throwing your life away,” she said simply. “That woman was going to destroy you.”

“She was carrying my child!” Rowan shouted, trembling.

Beatrice turned to him then, her eyes cold and almost pitying. “You’re too weak to understand. She wanted your name, your money, your future. You were a fool, Rowan. I simply corrected your mistake.”

He stared at her, horrified. “You killed her.”

Her shears paused mid-cut. “No,” she said softly. “We did. You signed the papers.”

Something inside him broke.

He left without another word.

Two weeks later, Beatrice Hart’s mansion burned to the ground in the middle of the night. The fire was ruled an accident, though some neighbors swore they saw a man standing in the rain across the street, motionless, watching until the flames consumed everything. He was holding something small in his hand — something that glinted faintly in the firelight before he turned and disappeared into the darkness.

Months passed. The world moved on. Rowan’s name faded from the papers. The Hart estate was sold, the family fortune divided, and his mother’s ashes buried in the same cemetery where Nyla’s family had erected a small, empty headstone for their lost daughter. Life, for everyone else, continued.

But one humid summer morning, in a small coastal town two hundred miles away, a woman went into labor at a roadside clinic. She refused to give her name, refused anesthesia, refused help. When the baby finally arrived — a girl with startling green eyes — the woman smiled weakly through tears and whispered, “Tell him we’re safe now.” The nurse, startled, asked, “Who should I tell?” But the woman didn’t answer. By the time they turned around, the bed was empty. She was gone.

When the staff cleaned the room, they found a burned photograph beneath the sheets — a man standing before a furnace, his hand pressed against the glass, eyes wide with something between grief and awe, as if he were seeing something inside that refused to die.

And for years afterward, the nurses at that small clinic swore that, every now and then, just before dawn, a woman’s voice could be heard humming in the empty nursery — low and tender, as if rocking a child that no one could see.

“Some love stories end with ashes. Others begin with what refuses to burn.”